Situational Awareness in Paddlesports

This article was written by Pete White for the University of the Highlands & Islands.

It is commonly understood that the dynamic world of paddlesports – coaching, leading or for fun – is reliant on constant, good decisions. Sometimes these decisions will be of an obvious nature, e.g. stopped at a big rapid deciding whether to run it or not, but other decisions we make may seem small or unconscious, such as on the move you shift to river left to get a better line.

What connects these different decisions is that they are based on context – we don’t make decisions for the sake of them, rather they are a response to something we have noticed. This picture of what we have noticed, is called Situational Awareness (SA) – and is key because it feeds the decisions that we make.

The concept of SA has been around for a long time. Initially used in the work of studying pilots, it has been applied to a wide range of tasks such as Air Traffic Control and emergency services. These jobs face environments which are complex, dynamic and may contain ambiguous goals. The most influential work in this area was by Endsley (1995) where she proposed a model of SA which was characterised by three different levels (Table 1).

Table 1 –

Three Levels of Situational Awareness

| Level 1 | Perception of the Elements in the Environment | Noticing or being aware of relevant elements in the environment |

|---|---|---|

| Level 2 | Comprehension of the Current Situation | Understanding the meaning of the elements and their relationship with each other |

| Level 3 | Projection of Future Status | Ability to predict future implications or workings of the elements |

This can be seen below (Fig i.).

The differing levels represent varying abilities of SA, which may be determined by a paddler's own knowledge, experience, and reflections. In the first level of SA the paddler will simply notice it is windy. It may be from feeling it on their face or the effect it has on their boat, or “seeing it” on the water – either way they just know that it is there. In the second level of SA the paddler would understand the significance of the wind and the effect it’s having on their goals – which is to go paddling and lead the group safely. Therefore, they can attach a meaning to the elements they are aware of. In the third level of SA they would use their understanding of the situation, to translate that into future action or implications. In this case they can see that the planned route is not going to work because of the danger the wind poses to a particular part of that journey.

It’s important to note that these differing levels are not a sequential process that we will all follow. The lower levels need to be part of the higher levels of SA – but just because you notice that it’s windy doesn’t mean that you will understand its implications. We need to view the differing levels as ways of describing our

level

of situational awareness rather than a

sequential process of situational awareness.

So, if situational awareness is a state that we exist in,

what are the processes that help develop this state?

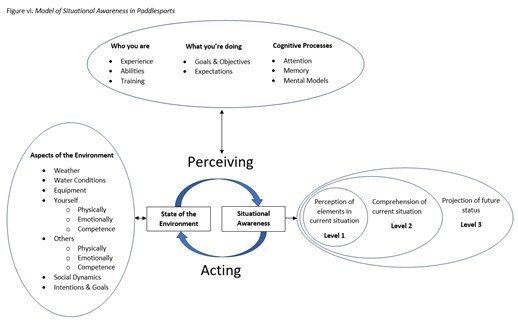

- Attention – through this we perceive and process different elements of the environment. We have it in limited supply, therefore we choose to direct the attention we do have to specific elements – this allows us to be more efficient in processing, but may lead to the loss of SA towards other elements.

- Memory – this affects how much information we can process. As we become more experienced, we use our long-term memory through the construction of mental models. Usually providing us with a mental short-cut, they allow us to direct our attention to specific elements that we consider to be relevant, to have expectations of what will and will not happen and provides a link between the situation and typical actions or decisions.

- Pattern matching – identifying links between critical cues in the environment and our mental model. Allows us to operate in the Level 3 SA as the “lower” components of SA are taken care of by the mental model.

- Processing – either we can be goal driven, directing our attention in line with our aims or we can be data driven, being open to environmental cues that show new goals are needed. The use of both is important as goals provide meaning to cues, whilst being open to new information stops us becoming fixated on a specific objective and becoming blind to new critical cues.

We could think of situational awareness as a state that we must have when required to make a decision, but that implies that it is something that we turn on and off throughout the day. Instead, we should view SA as something that we constantly have in life – just sometimes we pay more attention to it than other times. This constant interaction with our environment points to the process being cyclical rather than linear, raising the importance of feedback.

The model proposed (Fig vi) demonstrates the integrated relationship between the state of the environment and our situational awareness. Clearly the environment feeds our SA – equally the subsequent actions taken will influence the same environment, which will adjust our SA again.

So what…

Situational awareness is clearly intertwined with how we make decisions – if we are unable to have a good grasp of what is going on, even if we make a “good” decision, it would be on faulty information.

Below are some pertinent points;

- Source of many accidents – poor situational awareness has been attributed as the cause of many accidents in numerous domains. Within paddling it has recently been identified as a significant factor in sea kayaking accidents in Norway.

- Experience – the more we have, the more likely we are to hold more accurate mental representations, which allow us to direct our attention to the most important cues and identify the most likely course of action. It also allows us to hold more information in long-term memory, making it accessible through these schemas.

- Feedback – if we are not aware of the effects of our decisions, then we won’t know the accuracy of our perceptions that led to the situational awareness. Maintaining a cyclical relationship between our perceptions and actions allows our experiences to adjust and adapt our mental representations.

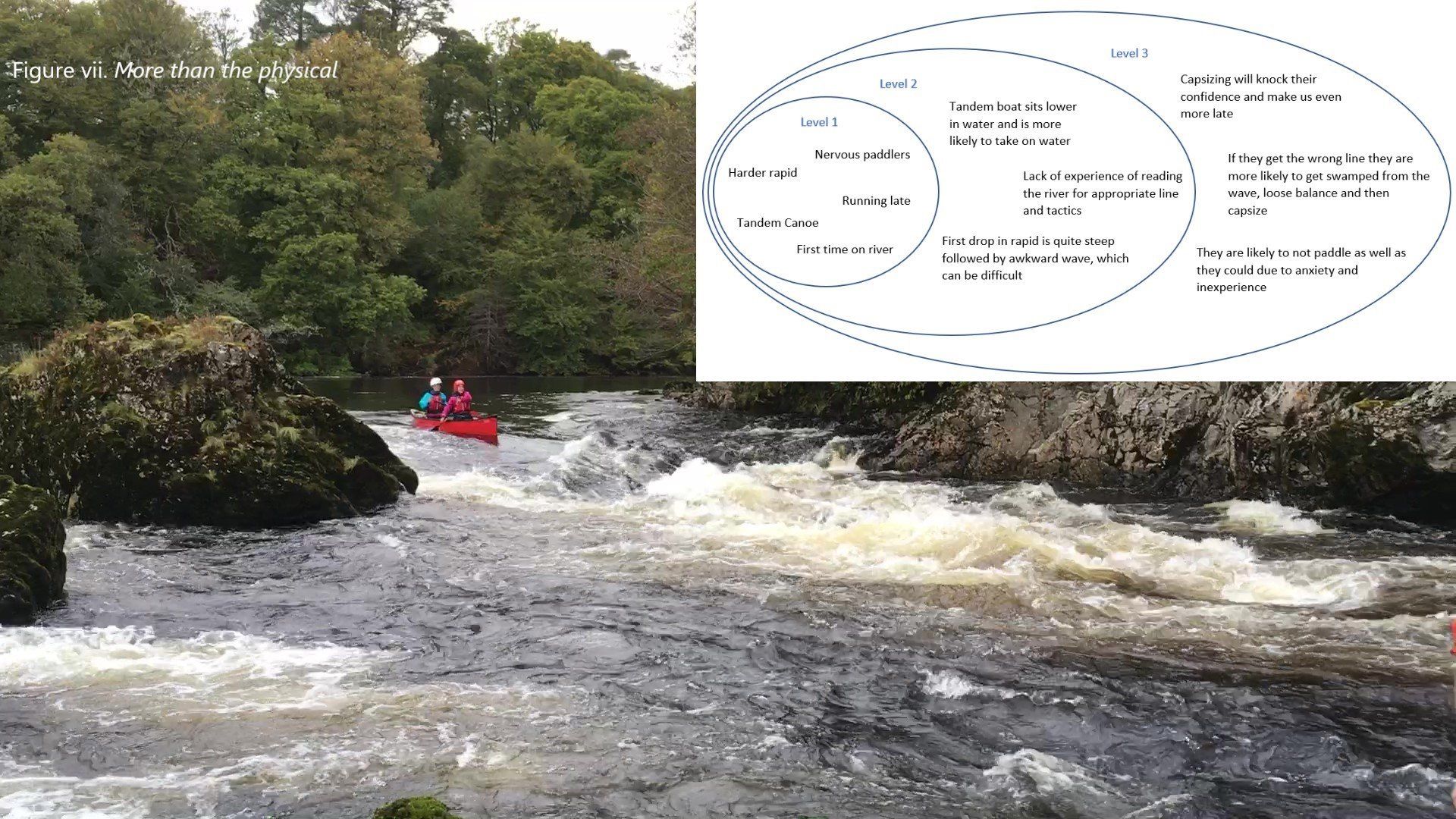

- State of environment is more than physical – the situation we encounter is not just the weather or conditions but is also influenced by ourselves and the people around us. This can be seen in Fig vii.

With these in mind, there can still be errors found in situational awareness such as;

- You may simply fail to perceive what is important until it happens. This may be due to lack of knowledge but may also be due to a narrowing of attention because of increased workload or stress.

- You may be unable to properly understand the meaning of the relevant elements in relation to your goals. This could be due to the lack of a mental model of the situation but also could be due to the selection of an incorrect model. This could be linked to a range of heuristics such as representational (cues that appear similar) or availability (the most recent mental model comes to mind).

- You may have an incomplete mental model of the situation and consequently struggle with performing mental simulations of what could happen.

Now what…

How are we able to develop good SA in paddlers and leaders? The British Canoeing qualification scheme provides numerous opportunities to both gain invaluable training, but also spend time with others on the water, sharing thoughts and experiences. What was suggested by Collins et al. (2020) was that use of pertinent questions such as – What is happening? Why is this happening? What does this mean for later? What might happen next? – may help develop a deeper level of thought, encouraging the development of Level 3 SA. This encourages us to all be more thoughtful and reflective in our discussions with one another, both on and off the water.

Our experience base is key to developing good SA. This is partly why with many qualifications there are minimum experience requirements for attending assessments – not as a demonstration of competence, but to articulate the amount of experience normally required to have a good understanding of the relevant environment. A danger for assessment candidates is that they view these as a tick box, doing the days without engaging in any thought throughout them. Additionally with the reduction in many pre-requisites for British Canoeing assessments (eg. Trainings, number of trips or coaching sessions) there is a risk that candidates will just turn up to an assessment without having the wider experience base required to deal with real life situations.

What is clear is that a positive culture within paddlesports and the wider outdoor industry is of great influence in the development of good situational awareness skills in aspiring paddlers. A culture that is inquisitive, open and thoughtful in the way it interacts with each other will help to encourage greater depth of thinking and reflection, whilst also being in the pursuit of genuine experience.

References

Collins, L., Giblin, M., Stoszkowski, J. R. and Inkster, A. (2020) ‘A study of situational awareness in a small group of sea kayaking guides’. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning. DOI: 10.1080/14729679.2020.1784765

Endsley, M. (1995) ‘Toward a Theory of Situation Awareness in Dynamic Systems’.

Human Factors

37 (1), 32-64

Kahneman, D. (2011)

Thinking, fast and slow.

New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux

Klein, G. (1998)

Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions. Cambridge: MIT Press

Zsambok, C. and Klein, G. (2014)

Naturalistic Decision Making. New York and London: Psychology Press

All images including Figure vi

Model of Situational Awareness in Paddlesports are owned and copyrighted by the author.